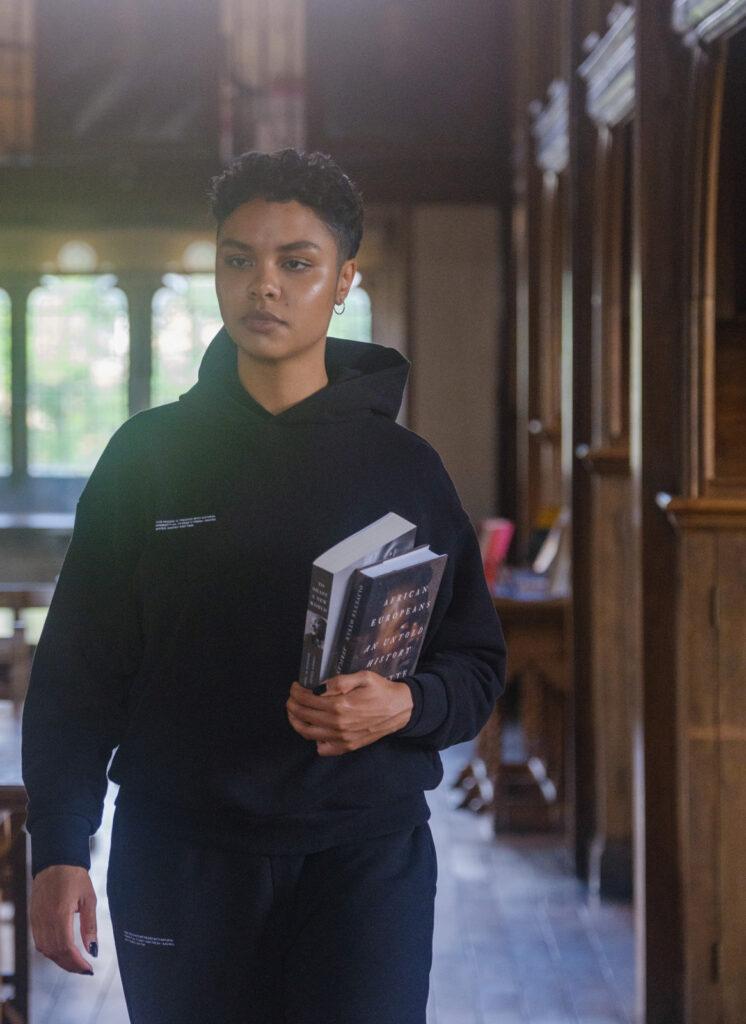

Delving into our passions can take us on unexpected journeys. Marie-Anne Leuty (she/her) speaks with Oxford PhD candidate Cerise Jackson (she/they) about how finding her research niche in Black anime brought her back to Tokyo.

Hi Cerise, what’s your area of research?

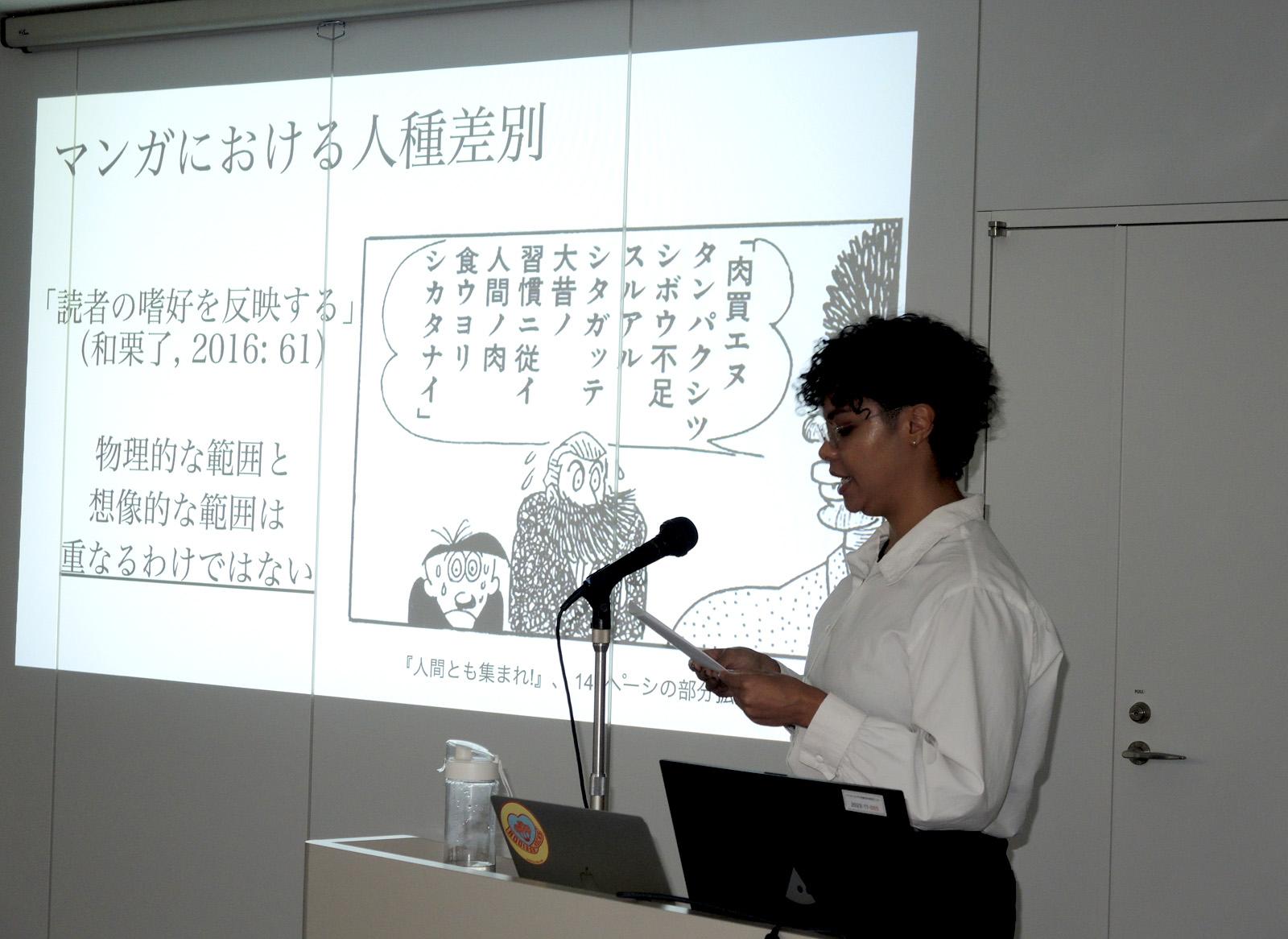

I am a transdisciplinary multidisciplinary researcher. My academic background is business then Japanese translation studies. Now I’m squarely in modern Japanese pop culture and translation studies – more specifically Black anime.

How did you first get into anime? Is it something you’ve always been interested in?

I wasn’t consciously into anime. I watched Dragon Ball and Pokemon as a kid in English dub. I really got into anime during my undergrad. At the time I was struggling with a host of issues: undiagnosed ADHD, a toxic relationship, substance abuse and traumas from my childhood which had resurfaced due to family issues.

I wasn’t attending classes and became quite isolated. I spent most of my time in my apartment and started watching anime. Black friends and colleagues kept telling me about it so an entry-level question that came to me was “why are all these Black friends watching anime and telling me to watch it in my time of need?”

Anime is very critical of society. It reflected where I was at the time with my business degree. Something about Black criticality synergises well with anime. They tap into disruptive themes. People have this perception that anime is airy and superficial – even very cute looking anime often has dark and societally conscious themes.

Intellectual anime created a safer space for my way of thinking than in university. I had no affinity with my business degree – it was just talking about capital, how to make more capital.

What was the turning point from anime being an interest to fully fledged research and study?

When I started my Translation Masters, the intention was to get better at translating, go back to Japan and make a bit more money than usual as a translator. My essays ended up dipping into Black anime. One of the first looked at the way Black characters are vocalised using lower Japanese dialects. My supervisors were very supportive and suggested I write about Black anime for my dissertation.

Independently, Black and anime are critical ideas. Anime is counterculture. There are many high Japanese cultures like literature and theatre that are given a lot of accolades from the West. Anime is seen as poor kid, angsty crap.

When you combine anime and Blackness together, you can fuck with anyone’s shit. It will pretty much fuck up most incumbent ways of thought. I enjoy fucking up incumbent ways of thought.

Was academia something you’d considered before? What direction would you have taken otherwise?

In academic terms, I’m maybe the person who’s making Black anime a thing but the phenomenon existed before me.

I’ve always been a critical, thoughtful kind of person. As a kid, I was flagged as gifted and talented but I never got to see anything through. I was dealing with so much shit: traumas, poverty, a broken family.

My grandma was a minister and I have a lot of gospel in my family. That doesn’t sound academic but it’s a kind of oral intellectualism, a vocal way of transmitting knowledge and resynthesizing thought in your mind. I used to do that out loud with my mum, hours just talking about something I learned. That’s always been an easier way for me to think about things. My father said that I wouldn’t end up being a singer in a choir, I’d end up being a preacher. Much to my chagrin because I wanted to be Beyoncé.

I don’t know if I’ll continue being an academic. If I could live any other kind of life, I’d be a monk in a mountain. I’d just be free to think and mull and contemplate and, you know, eat herbs or whatever they do. That’s my dream.

The one thing I’ve managed to be good at consistently is turning up to a question to dissect and give it a high level of critical insight. Essays don’t always come out right but when I get feedback from academics they go “wow, this is insightful, I don’t know how you got to this reasoning but that’s a great point”.

With the intersections that you represent, what specific challenges do you encounter in the world of academia?

I’m queer, Black-ish, diasporic on both sides. At times I feel like the poor side of me is probably just as problematic as the diasporic and racialisation.

At university it stands out when you didn’t go to a private or even a semi-funded school. It shows up in little things, minor traumas. One of the weirdest things to have to articulate is when people ask you what you’re doing for Christmas. They’re excited to spend it with their nuclear family and I’m like “well, I can go to my mum’s council house on the blow-up bed”. Not that there’s anything wrong with that – it’s just another way that I felt different.

In terms of my research, knowing who built Oxford and that my ancestors built it involuntarily – every brick irks me.

It’s challenging because you have to think and articulate in their way. If you make a point that doesn’t support their outlook, you have to argue it more than you would than if you made a point that did.

There are many parts that hurt.

At the same time, my intersections are a weapon and I feel obligated to use them. I think about the Black side and Croatian and Bosnian side of my family – white people also oppressed by colonial white powers. Oppression is something that unites more than separates us. I hope in the future that people who have experienced oppression come together in the face of it. Right now, we’re all very divided.

We have to understand whose house is mainly on fire. At the same time, we shouldn’t feel as if other marginalised groups can’t also aid the whole. The oppressor is always in the minority.

It’s how I undermine a lot of the incumbent thinking at Oxford. What they’re saying can’t be true. It doesn’t relate to me, my mother or my father or any of the people I grew up with so who does their narrative relate to?

What led you to study in Japan?

I have to learn Japanese. Don’t get me wrong. I love the language. There are very few sounds in Japanese, way less than most other languages. It sounds very clean to me, that’s the best way I can put it. I also wish it weren’t a prerequisite for my PhD. I don’t have a way of doing my research from a Black centred position. It has to be a Japanese centred position because there’s no Black cultural department at Oxford University.

My intent the first time I came to Japan in 2015 was to get as far away from Western society as physically possible. I taught English, worked in translation and localisation and stayed for three and a half years.

You’re currently based in Tokyo and pursuing advanced studies at the Inter-University Center for Japanese Language Studies in Yokohama, run by Stanford University. What’s it like?

It’s a one year Advanced Japanese course and only about sixty people a year get to participate. I wish anyone who’s interested in Japanese could do this. You could be a complete beginner and have at least an intermediate level of Japanese by the end – it’s that rigorous.

It’s been demanding but the support is there. There’s a humbleness about the teachers here that I really appreciate.

How would your day in Oxford compare to a day in Yokohama?

Oxford is very isolating. PhD students don’t have classes – we can audit a lecture if we want to but my normal day there is mainly me figuring out what to do. For someone with ADHD, coming up with my own structure and plan for my day is a nightmare.

Here, almost every moment of every day is structured. I log into my account and see my to-do list. It’s all there. I can simply work as opposed to thinking “where the hell do I even begin?”

It’s more about that gradual ‘kaizen’, doing things little by little, perfecting, perfecting.

In the UK, you have a big exam. Ahead of that there’s not much structure, it’s not particularly rigorous – as long as you can pass that big milestone, you’re good.

In Japan, there’s emphasis on little daily or weekly targets. At the start of every class we read one paragraph, answer two questions in ten minutes. Then it’s ten minutes on something else, fifteen minutes on the next exercise.

Most days we do ten minute presentations. If something goes wrong, the idea is ‘don’t worry, we’ll fix it later’ and then you do it again the next day and the next.

Do you feel a sense of home in Japan?

Definitely. My first experience here was running away from England. I got a taste for a simpler life. The idea of ‘the small happiness’ is another Japanese philosophy. Being happy with small things in your small apartment with your small cup of tea. There’s something comforting about smallness, not always trying to be as big and competitive or badass as possible.

In that way, I feel at home. I feel less anxious in general which is very weird because I’m in no way Japanese. I’m comfortable here.

What’s your experience been like creating a life for yourself in a new country?

Last time I tried much more to assimilate. I had my hair long and was much more femme presenting. I wanted to cause as little of a stir as possible. This time I’m not concerned with what people think.

Looking back I feel like I underestimated people here because it hasn’t remotely been a problem to just be me. No one’s particularly staring at me on the train because I’m a girl with shaved sides and puffy curls. I was perhaps doing a disservice to the Japanese by feeling like I had to be cute, soft and femme. No one makes a big deal of my existence, it’s really refreshing.

My teachers are wonderful and seem to respond very well to me being this eccentric, anime loving weirdo who’s loud in class. I’m holding more true to my identity than ever before.

What was your expectation of Japanese culture versus the reality?

When I was 14, I went to China for three weeks with school. It was total luck that a group of six of us went – one of our teachers got funding.

It was my first introduction to Japanese characters, which are originally Chinese characters, in a calligraphy class. We went to temples – Buddhism is prevalent in the history of both countries. There are a lot of parallels with the food. China was a good primer for my expectations in Japan. There’s this juxtaposition of ancient temples and ceremonial traditions alongside high-tech sprawling cities and high-speed transport infrastructure. Anime also introduced me to Buddhism, Japanese shinto and other countercultural spirituality.

The separateness between China and Japan, not to mention Korea, because of these nation-state identities is a whole different conversation, as well as the wars and colonialism between them. There’s a lot to unpack and learn. At the same time, China made me feel like I could survive in Japan and more importantly, away from the West. If it hadn’t been for that experience as a teenager, I doubt I’d be here now. I wish more young, disadvantaged youth could have these opportunities.

Finally, what is your definition of home?

If my ministry is made of what I think it is then home is not binary: it’s a journey and a destination.

There’s the moving, the breathing, animated journey of searching for and creating ‘home’ wherever you are. But I think we will all eventually find that stable, that truest spiritual home, in the heart. So it is also a destination.

Follow Cerise: @cerisejackson