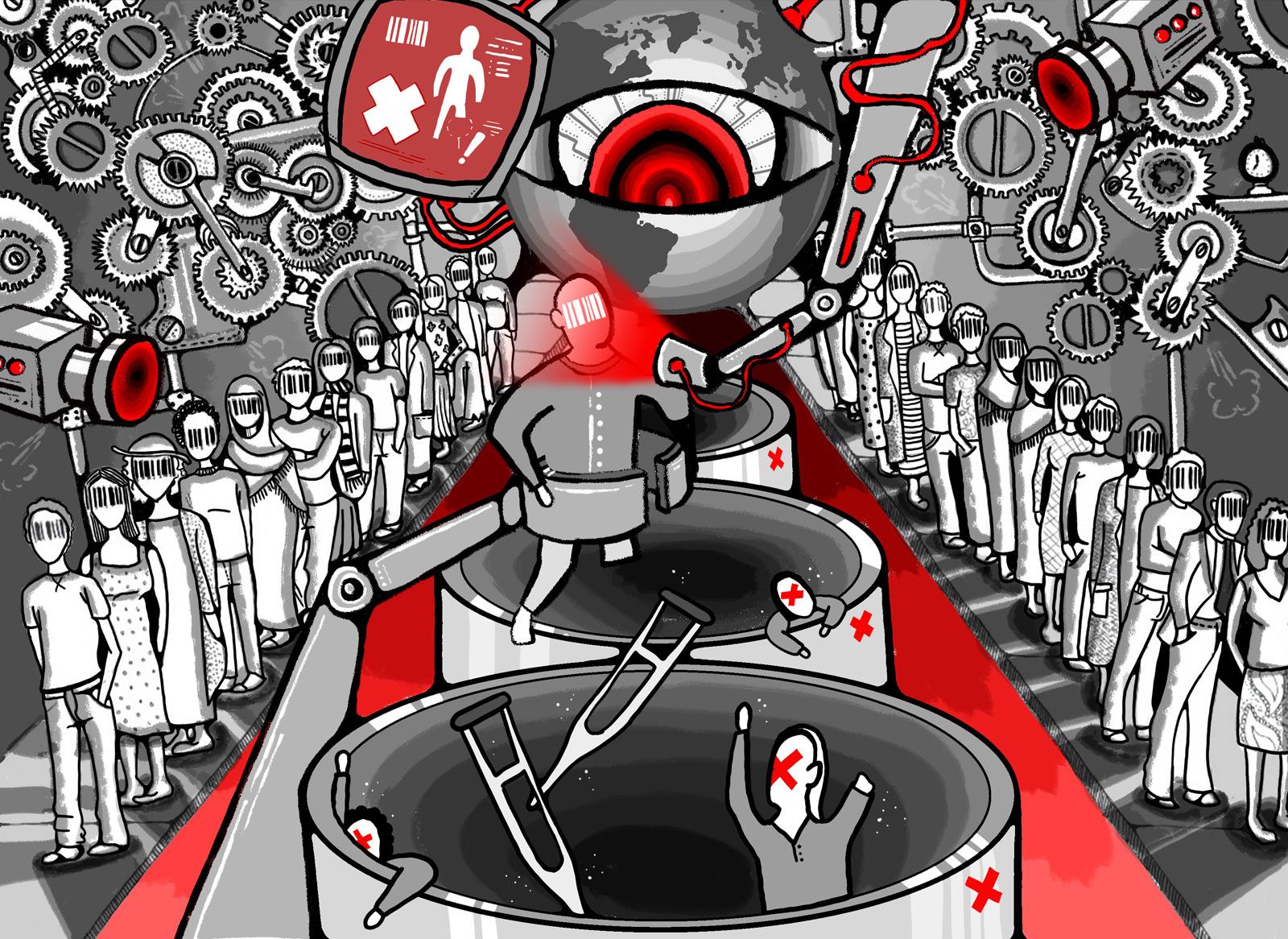

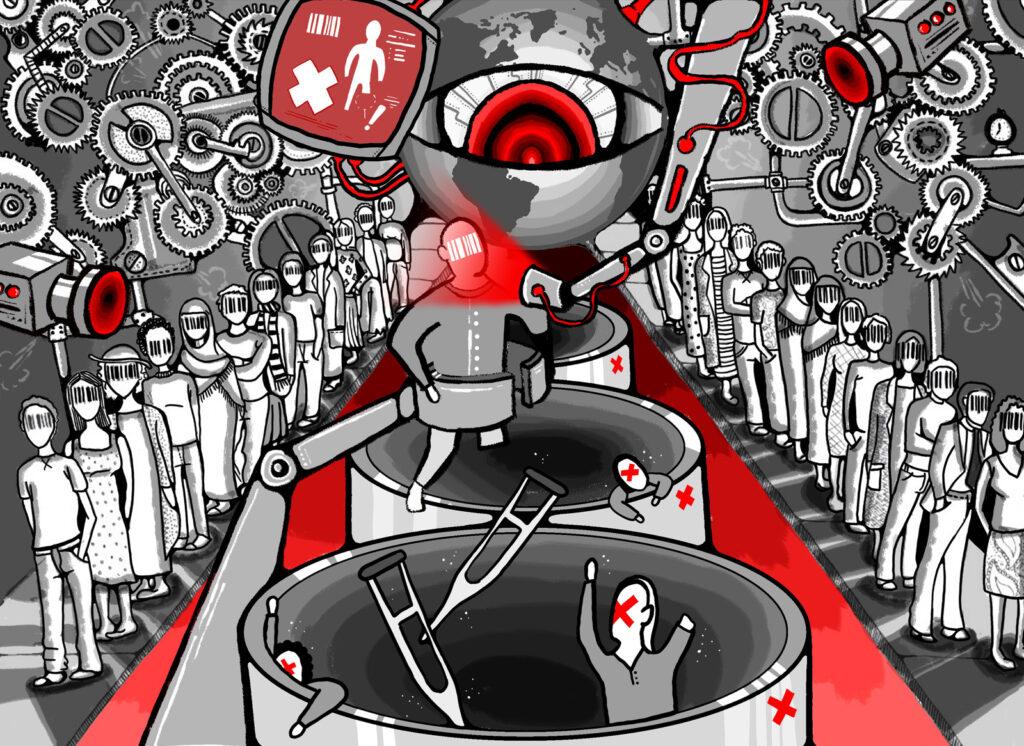

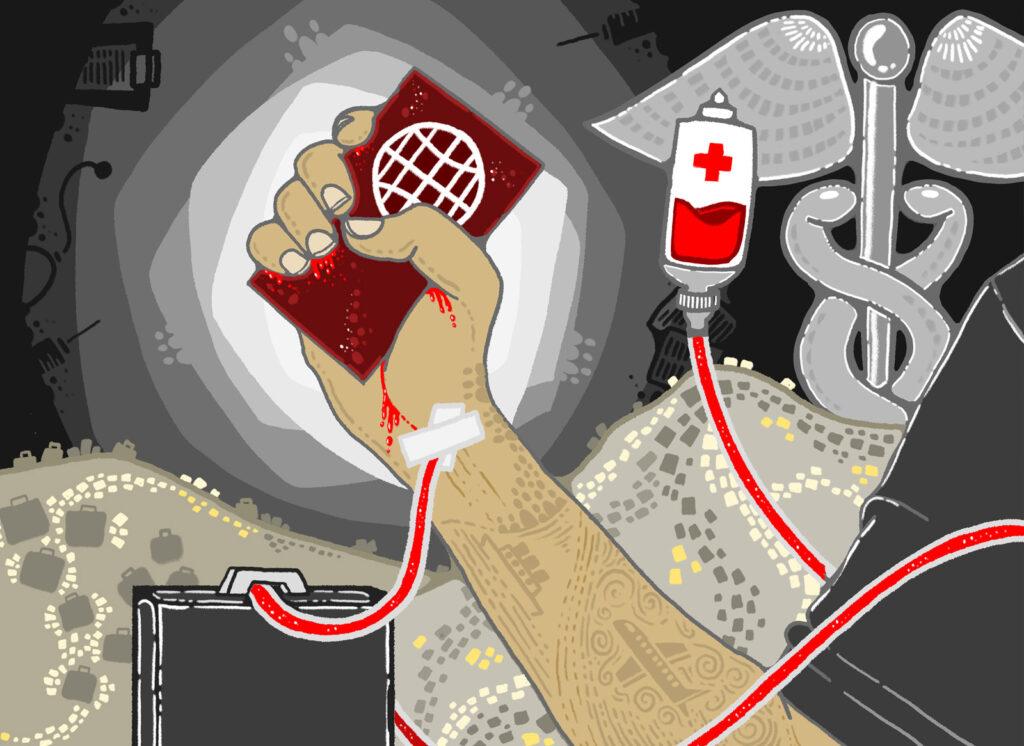

Access to healthcare has come under the microscope since 2020. Disparities between those who have Covid-19 vaccines available to them – and those who don’t – throw into sharp relief how fragile our public health systems are.

With vaccination status already having implications on how people go about their live, how might things look if we overtly use health status as a marker of wider rights?

In Canada, medical otherness already impact lives at a bureaucratic level, playing a pivotal role in the country’s immigration process.

Marie-Anne Leuty speaks with Dr Laura Bisaillon (she/her), a recent fellow at NIAS, about medical inadmissibility – a colonial legacy that determines immigrants’ right to permanently settle.

“If the late Stephen Hawking had wanted to settle in Canada, he would likely have been denied because he was disabled.”

The stark opening statement to Dr Bisaillon’s research project leaves a lot to unpack.

Widely thought to be more welcoming to migrants than its continental counterpart, one might think that Canada has a more inclusive approach to immigration than the United States. A range of attractive work permits abound for working holidays, students, young professionals, highly skilled workers…

But when it comes to settling permanently, an additional factor comes into play known as medical inadmissibility.

“Medical inadmissibility is a decision making process,” explains Dr Bisaillon. “It’s an institutional barrier to certain types of bodies when applicants file for permanent, and sometimes temporary, residency to Canada. It’s an institutional process that acts to allow some people in and filter others out.”

It’s existed as a practice in Canada since 1867 – a period that coincides with the rise of medicalisation and the beginnings of psychiatry.

On arrival at ports such as Halifax, state-sanctioned doctors assessed new migrants to determine if they were sick with an infectious disease, had a disability or any discernible mental or physical otherness that would make them a charge to the state.

The methods used to filter out people weren’t exactly systematic in the 19th century. Doctors would cast an eye over queues of people and make a call on anyone who didn’t fit their archetype of health and productivity based on standardised criteria. Deportations based on medical otherness were rare, however boat companies leaving Europe for Canada could face fines for giving passage to those deemed unfit.

Fast forward to the current day and these practices still exist, albeit with modern medical diagnoses and complex bureaucracy.

Dr Bisaillon first came across the term ‘medical inadmissibility’ in 2006 through her work as a social worker supporting women, including refugees, with HIV. She explains that:

“HIV screening is mandatory for all permanent residency applicants. Working with these women, I started to understand the application processes they had to go through and the broader regime that impacts anyone who is bodily other.”

by Aida Radoncic and Ujwal Mantha

by Amy Zhang and Ujwal Mantha

The range of bodily otherness encompasses conditions from Down’s Syndrome to autism to cancer. In short, anything diagnosable can potentially make someone ineligible to settle permanently.

What does the process look like?

“Medical exams are one of the earliest stages of the immigration process but they’re only valid for a period of six months. You find that people pay multiple times for exams which increases the chance of them being diagnosed with something – it also becomes very costly.”

At approximately $200 per exam, and with the majority of testing taking place outside of Canada where applicants are based, Dr Bisaillon likens this area of transactional medicine to a Wild West with little to no monitoring.

Her research is the first of its kind and focuses on the work of doctoring, specifically because of the importance that Canada places on medical analyses in its immigration process.

It shows a worrying level of ethical compromise.

by Amy Zhang and Ujwal Mantha

by Amy Zhang and Ujwal Mantha

“What I find in cases with HIV, for example, is that certain services and forms of care simply aren’t happening. The basis of testing is exclusion – doctors are looking for reasons to write up a report to reveal conditions and medical otherness that the applicant lives with.

“These medical encounters are not about caring for a patient. They’re about clinicians becoming bureaucrats filling in forms. That’s disturbing especially when people I’ve interviewed say that the doctor wasn’t very nice or rushed through tests.”

General practitioners become decision makers and their labour contributes directly to the work of other key figures: lawyers, visa officers, other doctors. Even notes made in the margins of diagnostic tests inform decisions further down the line.

This has huge implications for applicants.

To show the real-world impact, Dr Bisaillon worked with a team of students from the University of Toronto to produce an animated documentary called ‘The Unmaking of Medical Inadmissibility’ highlighting a handful of stories about people caught up in the process.

One of them is Martha.

A woman of African origin, living and studying in Russia at the time, she was an attractive candidate with near completion of a doctorate in Applied Sciences. Fluent in English and French (Canada’s official languages), two African languages and Russian, all this stood her in good stead in a points-based immigration system.

Six weeks after her initial interview and tests, she got a call. Something came up in her medical. She suspected that she had tested positive for HIV.

An immigration application three years in the planning instantly became riddled with complexity. In addition to the personal impact of a positive diagnosis, she understood that she would be subject to disease-specific state surveillance. Living in Russia, where non-nationals who are HIV positive are expelled, this also meant that she would have to return to her home country where access to medical treatment is limited.

Another woman, Stella, also had a troubling experience.

Originally in Canada on a work visa, she was employed as a hospice nurse caring for elderly people. She was a single mum to a young daughter who, over four years, had socialised into a new culture and life, had a strong circle of friends and was doing well at school.

Stella naturally wanted to ensure more stability for her family so applied for permanent residency. However, medical tests showed that her daughter had a disability. The cost to the state of caring for her young daughter outstripped the value of Stella’s work in the care sector. ‘Excessive demand’ on medical or social services justified the outcome. The life Stella and her daughter had built in Canada came to an abrupt end as they returned to their home country.

by Ujwal Mantha

by Ujwal Mantha

With millions of applications per year, terms such as ‘excessive demand’ reflect a system so large that individual human stories are disregarded.

“Most Canadians are unaware of this situation,” explains Dr Bisaillon. “But when the majority of people talk about immigration more widely, economics often comes up as the main justification for how things play out.

“I think that it’s a reflection of how our societies generally have moved since the 1980s and the start of neoliberalism. Our collective awareness links worth to commercial and financial output now more than ever. We’ve diminished our value by equating ourselves with a dollar or euro sign.”

So with the high level of medical ethical compromise, why does this disabilist practice continue to hold such sway in settlement applications in 2021?

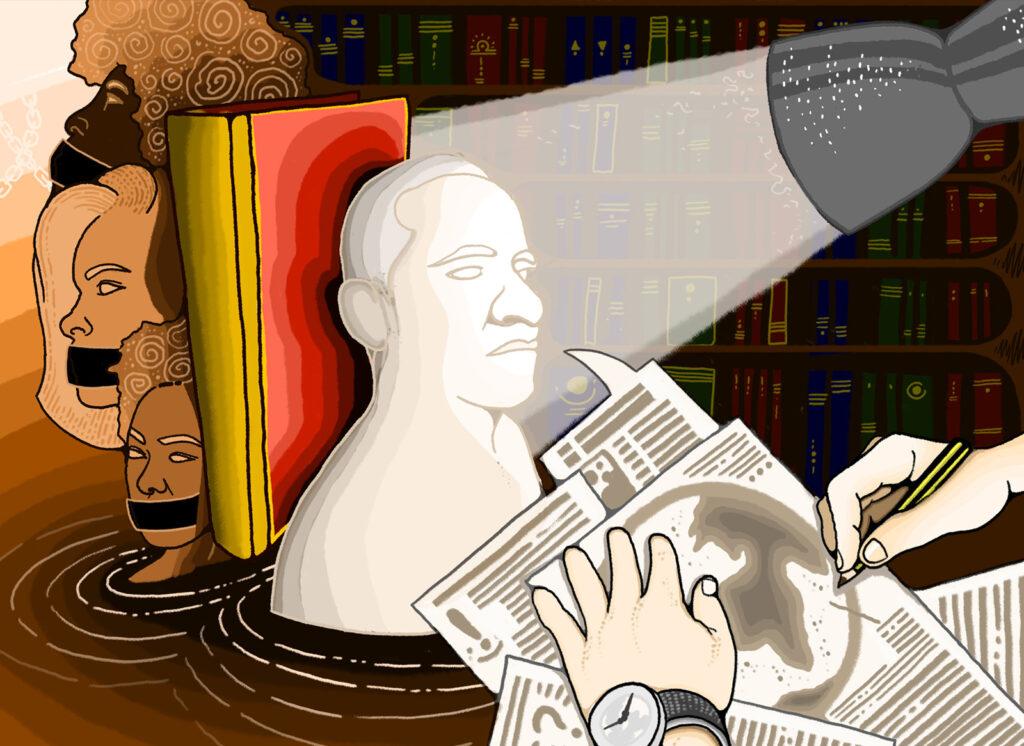

Another distinct element of British colonialism is the fetishisation and problematising of the body. As Dr Bisaillon explains:

“Compared to other colonials, say the French, Belgians or Italians, there’s a peculiarly intense obsession with cleanliness attached to morality in British imperialism. There’s a long-standing relation with the body, how it functions, its senses, smells, condition and fitness that filters into public health policing.

“These ideas of cleanliness and fixation on the bodily condition continue to play out and perpetuate problematic practices that are written into law. It’s now time that we see that and start to disassemble those practices and policies.”

by Ujwal Mantha

by Ujwal Mantha

Couple these ideals around the body with a protestant work ethic – another legacy of British colonialism – and we see how the correlation between bodily condition and productivity is baked into the fabric of immigration policy. In essence, the harder you work, the better you inherently are and the more value you hold – the same disablist logic instilled into neoliberalism.

Whilst centring doctoring in her research, did Dr Bisaillon’s findings reveal how race plays into these practices?

“I didn’t do a racialised or gender-based analysis as it was important to get a baseline of how medical inadmissibility applies to all bodies,” she explains. “However, it quickly became obvious that geography plays a significant role with the immigration system favouring people from more affluent countries.”

Economic and geographic factors matter in immigration systems rooted in British colonialism. Historically these favour wealthy, industrialised countries with majority white populations.

These factors play out at every level of the application process.

An applicant would need to be fluent in one or both official languages (English and French) to score higher in Canada’s points-based system. You’d need to be in an urban area, or at least be able to physically get to a test centre with a designated doctor. You’d need to be able to afford the fees.

HIV tests aren’t the only mandatory tests – there are three in total (the others being tuberculosis and syphilis). Most African countries, with the exception of South Africa, don’t have broad access to these tests so the inequalities of geography impose screening out of African bodies immediately. As Dr Bisaillon summarises:

“Whether the Canadian government acknowledges or realises this I can only speculate. What I am able to say is that these effects have a racialised effect as inadvertently, advertently or otherwise, a whole continent can be excluded as a result of these barriers.”

by Ujwal Mantha

by Ujwal Mantha

As we grapple with a worldwide health crisis, Covid-19 reminds us what people with bodily or developmental otherness have long known. That fragility leads to discrimination and prejudice, and the remedy to this is heightening sensitivity and empathy towards others.

Those whose lives have been turned upside down at the hands of an immigration system wedded to medical inadmissibility bear the brunt of a lack of awareness and care that those born in economically stable and affluent countries take for granted.

What does Dr Bisaillon hope people take from the film created by her and her team?

“I want them to be shocked. I want them to learn something. I want them to be bothered and to see this as a humility check because we all know someone with a heart condition. We all know someone who’s had Covid. We all know someone with HIV – even if we’re not aware they’re living with it.

“As humans who are imperfect, frail and on this Earth for a short time, I hope to move people.”

Dr Laura Bisaillon – Ph.D. from University of Ottawa recently completed an Individual Fellowship at Amsterdam-based NIAS (Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study in the Humanities and Social Sciences).

She is Associate Professor of Health and Society at the University of Toronto Scarborough.

To find out more about medical inadmissibility, and the visual glossary images included in this article, visit www.canandamedicalexclusion.com.

Dr Bisaillon’s book “Screening Out: HIV Testing and the Canadian Immigration Experience”, published by the University of British Columbia Press, is due for release in 2022.

Follow Laura: @laura.bisaillon

Follow NIAS: @nias_knaw

CREDITS

Produced: The Inadmissibles Art Collective

Direction + Research: Dr Laura Bisaillon

Written: Dr Laura Bisaillon + Aida Radoncic

Story Boards + Animation + Illustatrations: Ujwal Mantha, Tania Montoya, Aida Radoncic, Ze Xi Ye, Zihan Yi + Ke Er Zhang

Sound Design + Editing: Zihan Yi